Ride Into History: Kim Jeong Suk

Family and Nationhood

The guerilla unit, part of the Northeast Anti-Japanese United Army, was on the move in Manchuria, under the command of Kim Il-Sung, the man who would be king. In the Stalinist sense of the word, of course. Assassins intent on taking the leader’s life approached, probably factional or ideological rivals from within the various communist groups active in Manchuria at the time, because you know if they were Japanese, North Korean propaganda would have crowed about it endlessly. As it is, they restricted themselves to “enemies” and left it at that. Kim Jeong Suk, Kim Il-Sung’s erstwhile comrade in arms and partner, acted immediately, shooting one, while Kim Il-Sung took care of other. I like to imagine Kim Jeong Suk, then, striking a gangster pose with her revolver, eyes all crazy, informing the man she’d just shot that she reserved the right to shoot her man for herself, and she couldn’t just allow any old raggedy-assed rival communist to go around capping her boyfriend. Standards, after all, need be maintained. Or something like that. And hell, there may even be a grain of truth in the story somewhere. It does make the point that Kim Jong Suk was no shrinking violet, though, really quite well.

Kim Jeong Suk had moved to Manchuria young, probably with her mother, in search of her father, who had gone on ahead for work. She ended up an orphan, maybe due to the Japanese authorities killing her mother. The story is murky and comes from North Korean sources, so distortions are likely. Like seemingly all of the Koreans involved in the foundation of both South and North Korea, though, she had run ins with the Japanese authorities and may have been imprisoned. What is certain is that she joined the communist guerilla group, the Northeast Anti-Japanese United Army, that her future husband was a part of, sometime in the 1930s, when she was in her late teens, where, in addition to her side gig of popping a cap in anyone attempting to take down her future husband, she cleaned, sewed and cooked.

The cooking part is prominent, in that Kim Jeong Suk is a woman frequently associated with food, with Russian officers who visited her home to meet with her husband recalling her excellent cooking with evident fondness, while Russian women from the area surrounding the Red Army camp where the Kims lived in the early 1940s remember her coming to their village to trade army rations for fresh food. Around 1941, Kim Jeong Suk married Kim Il-Sung in the USSR, and in that same year, she gave birth to a child named Yuri Irsenovich Kim in Soviet documents, known as Yura in the family. Those Russian village women in the far reaches of Siberia, trading food with the wife of an ethnically Korean Red Army officer, specifically mention a small boy who accompanied his mother on her outings, holding her hand while still little more than a toddler. A baby born in a Red Army camp in Siberia, in the Soviet Union. An infant who would grow to be a man known to the world as Kim Jong Il.

It seems like an insignificant detail, a little boy going out with his mother on trips to replenish the family pantry, but it’s actually quite significant. The birthplace of Kim Jong Il, that is. North Korean propaganda has him being born on the slopes of Mt. Baekdu, on the border of Korea and China, in a secret guerilla base established there by his parents in their fight against the Japanese, whereupon a double rainbow was seen in the sky, after the appearance of a bright shining star. Basically, what is going on there is the foundation of the Baekdu Bloodline myth, and that’s quite a serious thing.

Mt. Baekdu is a beautiful mountain that is scared to Koreans, an extinct volcano on the border with China with a scenic crater lake. Photos of the mountain’s crater lake often feature on the kind of large Korean wall calendar that I always seem to see in a certain type of Korean restaurant, the type of eatery I prefer, with a casual server, unpretentious—some might say outdated or shabby—furnishings and by far the best Korean food available on the peninsula. Mt. Baekdu is a visual image inextricably linked to Korean nationhood, somewhat like Ayers Rock, Uluru, and the 12 Apostles are to Australia.

The mountain is the birthplace of the Korean culture hero Dangun, the mythical founder of the Korean nation. Thus, as the mountain is Kim Jong Il’s supposed birthplace, in the propaganda stories he is being symbolically linked to Dangun. This is of critical importance, as it is one of the ways that North Korean propaganda seeks to legitimize the continuing rule of North Korea by the Kim family. It’s been called the divine right of Kims—and that’s nowhere near original—as, like the divine right of kings, it seeks to legitimize unelected leadership through a form of divinity, in this case equating Kim Jong Il with a man, Dangun, whose father Hwanung was a supernatural being placed on earth by his fathr, a God, and who turned a bear into a woman and made her his wife, Ungnyeo, the woman who would be Dangun’s mother.

Kim Il-Sung was to go on to build a mausoleum to Dangun in the early 1990s, a communist ziggurat completed in 1994, the year of his death, after North Korean archaeologists discovered Dangun’s supposed remains near Pyongyang. Once again, they’re trying to link the founder of the Korean nation to the current capital and ruler of North Korea. In cases like that, where they make some wild improbable claim, the international press often laughs at them. The thing is though, in the same cases, truth and fiction are just not important. The archaeologists are obviously incentivized to find Dangun’s remains etc. What is important is the narrative, the building up of the Kim family through traditional icons. The western media publishes a funny story about a weird regime on the other side of the world, seeing what is being claimed, but never truly understanding why they are claiming it.

Again, in 2012, in a report widely ridiculed and covered in international newspapers, it was reported that the North Koreans had discovered a unicorn’s cave. There, the term “unicorn” was a poor translation of 기린 or Girin, a mythical beast from East Asian mythology. The whole unicorn cave narrative was entirely misunderstood by the international media, again taking a seemingly nonsensical North Korean claim at face value and having some fun laughing at its ridiculousness, without even trying to dig deeper to find the underlying meaning that is there. There are always reasons that the North Koreans do the things they do, even if they often come across as nonsensical to outside observers. The media supposed that the North Koreans were trying to say that they had found an actual unicorn, a mystical horse with a horn on its head, or were trying to provide a scientific basis for the existence of unicorns and laughed it off as just another wacky North Korea story. It’s like Kim Jong Il’s famous eleven holes in one on the golf course, a story much embelished and then published, seemingly without a responsible adult ever stopping to examine the circumstances surrounding the narrative and trying to provide context. In the case of the North Korean unicorn, the Girin is a beast known in mythology to have only appeared to the wisest of rulers. The sudden discovery of this mythical beast’s cave near Pyongyang, upon the ascension of the virtually unknown communist prince, Kim Jong Eun, to the North Korean throne is obviously not a coincidence. It’s exactly the same thing as changing Kim Jong Il’s birthplace or discovering Dangun’s remains, it’s an attempt by the North Koreans to link the modern rulers of North Korea, the Kim family, with ancient Korean rulers in a form of nationalistic mysticism. It can also be seen as almost a coded means of reassuring the North Korean populace that their new leader is a wise and sensible young man, as a Girin had suddenly appeared to him, in a manner of speaking. A cave bearing the Chinese character for Girin had been discovered, and thus, a mythical beast had symbolically appeared to the new leader. I’m sure the overtly militaristic North Korean faction propping up the new leader had a team of stone cutters out at some cave cheerfully carving a Chinese character into the stone there, before being sent to the gulag, lest they open their mouths to anyone.

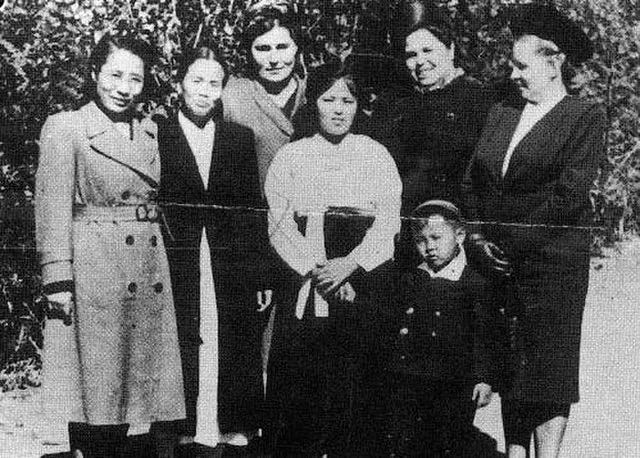

North Korean propaganda is frequently fanciful, but there are some things that seem to be accurate. Kim Jeong Suk was to give birth to another son in Russia, the short-lived Alexander “Shura” Kim, and then to a daughter, Kim Gyeong Hwei, in 1946, in Pyeongyang. In 1949 she was to pass away in traumatic childbirth as she delivered a stillborn daughter. Her husband married his second wife, Kim Song Ae, after Kim Jeong Suk’s death, and the new spouse appears to have been somewhat touchy about the subject of his first wife. Thus, Kim Jong Il’s mother all but disappears from North Korean propaganda for the span of around four decades.

In one of those weird North Korean Orwellian revisions of history, the memory of Kim Jeong Suk was to be rehabilitated when her son took power and revived the remembrance of his beloved mother, the woman whose hand he had held as a small boy growing up in an army camp in Siberia, who had healed his hurts and made him small treats to eat. Even monsters love their mothers, and it is the monstrous acts of the rulers of the North Korean state that jerk you out of your complacency at times. Reading about the Kims, sometimes you have to remind yourself of their actual nature, when at times they can seem quite relatable. As a small child named Yura, Kim Jeong Il was not yet the weird film obsessed dictator he was to become, overseeing a system of prison camps as brutal as any ever witnessed in the world, all while enjoying lavish spreads of imported food and alcohol as the people of North Korea endured famine and died of starvation, trying to eat tree bark and various other things to survive.

You sometimes wonder what Kim Jong Suk would think of her legacy and her family’s deep strangeness. Her grandson, Kim Jong Eun, just unveiled his daughter Kim Ju Ae, Kim Jeong Suk’s great granddaughter, a little girl just like one of my son’s playmates. Speculation is rampant as to the meaning behind the girl’s introduction to the world, whether she’s his political heir, whether he is feeling confident enough to show off his family due to his increasingly sophisticated nuclear arsenal and military support or whether he just loves his daughter. One thing that is certain though, is that the dynasty created by Kim Il-Sung and his first wife Kim Jong Suk continues to be of great relevance and interest all of these years after her untimely demise.

In the Ride Into History project, I am on my bicycle (sometimes) and examining the Korean War and the history of Korea in the decades thereafter and therebefore, from explorations of the legacy of the war in modern Korea to deep dives into the past. So why not come along for the ride? Subscribe to receive regular email newsletters in your inbox, as well as offerings such as photographic, audio, and video content.